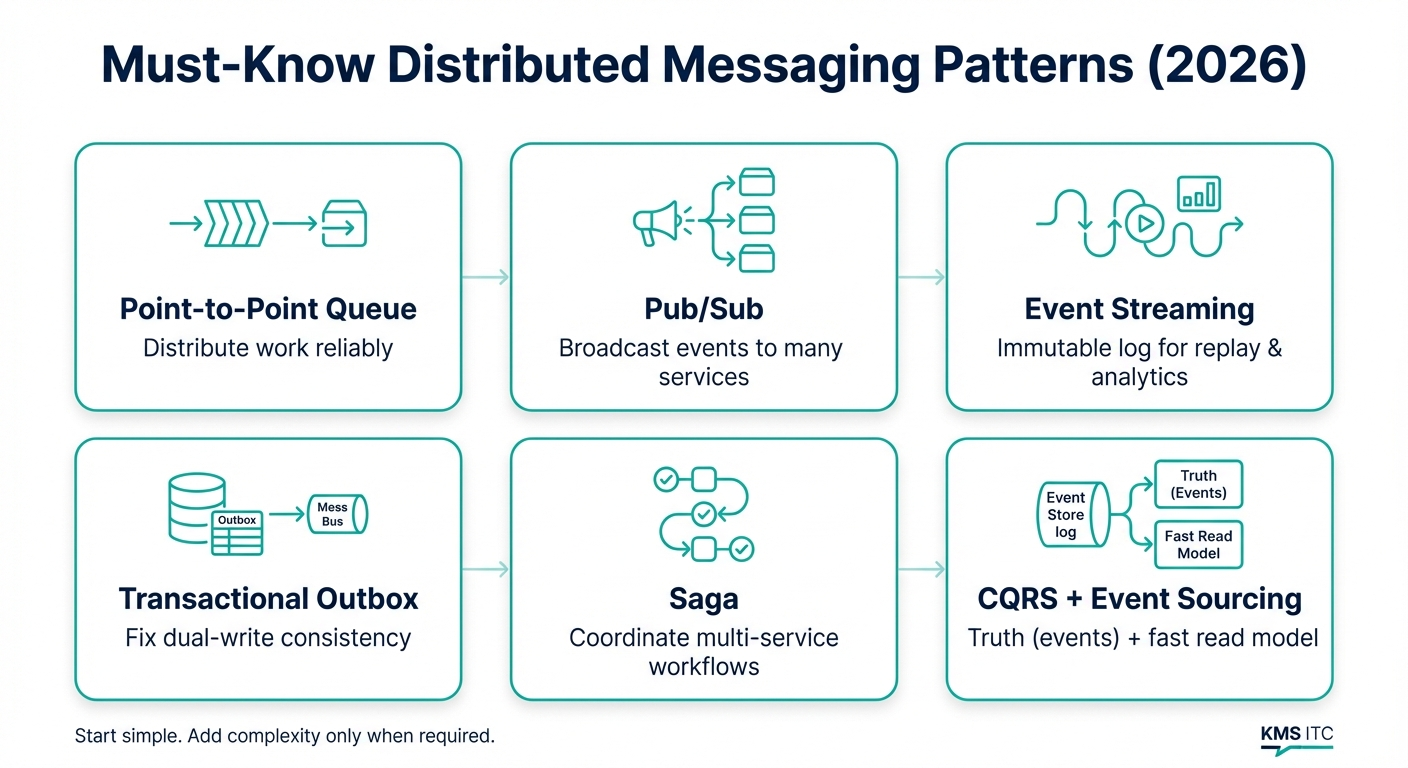

Beyond Request–Response: Distributed Messaging Patterns for 2026

Synchronous HTTP across microservices creates brittle distributed monoliths. Here’s a practical guide to modern messaging delivery models, outbox, saga workflows, and when CQRS/event sourcing actually makes sense.

KMS ITC

In a monolithic world, life was simple: a function call happened, a database updated, and a result returned.

In today’s distributed microservices landscape, that simplicity becomes a liability. Overusing synchronous HTTP calls creates distributed monoliths—systems that are brittle, slow under load, and prone to cascading failures.

To build resilient systems, we need to embrace asynchronous messaging. This article covers the mainstream patterns that govern how modern services communicate, maintain consistency, and scale under pressure—without turning your architecture into an un-debuggable science project.

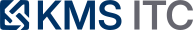

1) The foundation: delivery models

Before we talk about consistency, we need to understand the “shape” of message delivery.

Point-to-point queue (the workhorse)

A producer sends a message to a queue. Even if multiple consumers are listening, exactly one processes the message.

Best for: background job processing (invoice generation, image resize, email send), and any workload you want to distribute across a worker pool.

Publish/subscribe (the broadcaster)

A producer publishes an event to a topic. Every subscriber gets its own copy.

Best for: notifications and state sync. Example: OrderCreated goes to Shipping, Email, and Analytics.

Event streaming (the time machine)

A stream (Kafka-style) keeps an immutable log for a period. Consumers can replay history.

Best for: real-time analytics, auditing, and state reconstruction.

Rule of thumb:

- Queues = “do this work”

- Pub/sub = “this happened”

- Streams = “this happened, and we may replay it later”

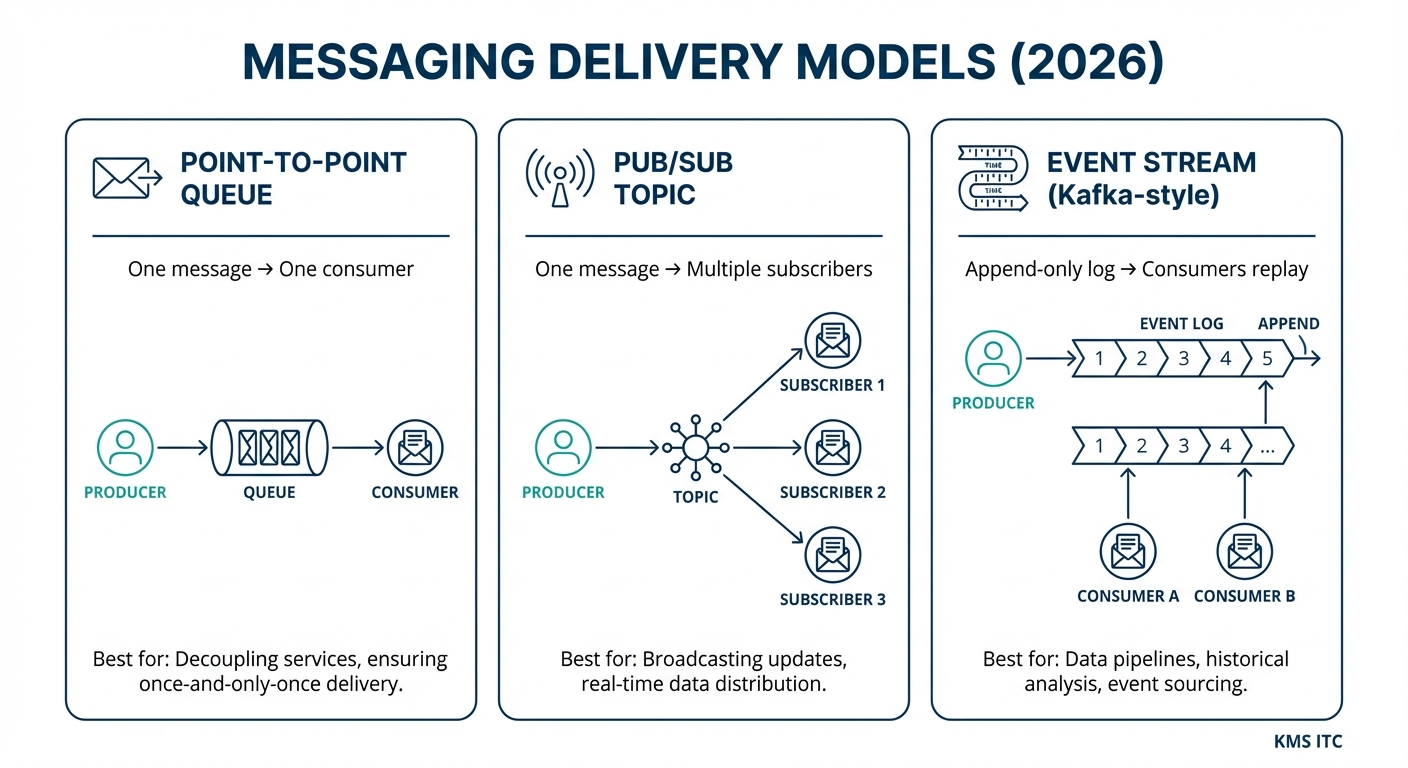

2) The dual-write problem: Transactional Outbox

One of the hardest problems in microservices is ensuring a database update and a broker publish happen “atomically”. If your database commits but the broker is down, your system becomes inconsistent.

The Transactional Outbox pattern solves this by:

- Creating an

OUTBOXtable in your service database - Saving business data (e.g.,

Orders) and the event payload (e.g.,OrderCreated) in the same local transaction - Using a relay/CDC tool (polling or Debezium) to publish committed outbox events to the broker

What you get:

- Reliable at-least-once publish

- No “silent inconsistency” when the broker is temporarily unavailable

What you must do:

- Make consumers idempotent (duplicates will happen)

Practical idempotency techniques:

- store processed message IDs (dedupe table)

- use natural idempotency keys (orderId + eventType + version)

- ensure handlers are “upsert-like” rather than “insert-only”

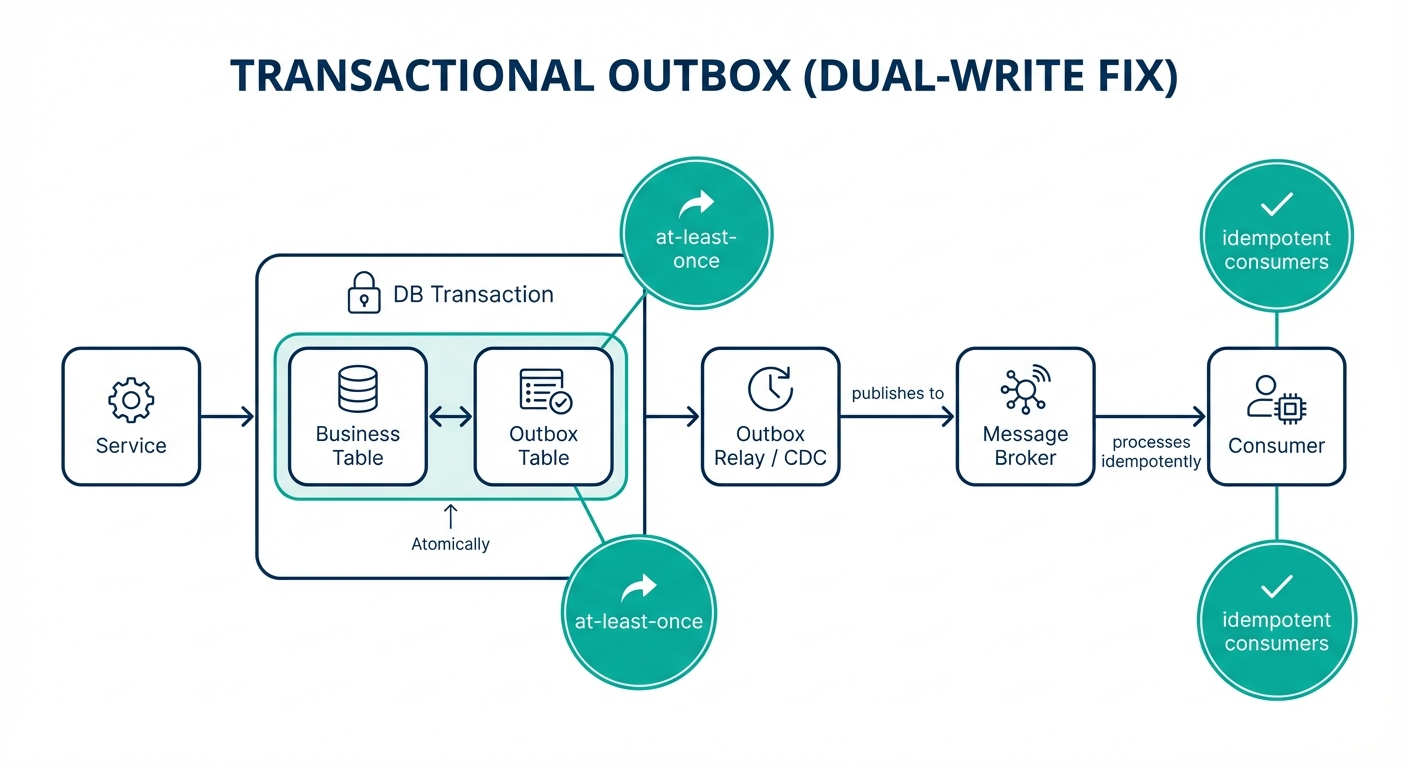

3) Distributed workflows: Saga pattern

When a business process spans multiple services (e.g., booking a trip across Flight/Hotel/Car), you can’t use a global ACID transaction.

A Saga is a sequence of local transactions. If one step fails, it runs compensating transactions to undo earlier successful steps.

Choreography (decentralised)

Services listen to events and decide what to do next.

Pros: very decoupled.

Cons: harder to trace as workflows grow.

Example flow:

- Order Service emits

OrderCreated - Payment Service emits

PaymentSucceeded - Inventory Service emits

InventoryReserved

Orchestration (centralised)

A central orchestrator issues commands and tracks state.

Pros: easier to monitor/debug; clearer ownership.

Cons: introduces a central “brain” you must build and operate.

Example flow:

- Orchestrator →

ChargeCard - Orchestrator →

ReserveInventory

When to choose which:

- small/loose workflows → choreography is fine

- complex/regulated workflows → orchestration is usually easier to govern

4) CQRS & Event Sourcing (use deliberately)

These are powerful, but they are not defaults.

CQRS

Separate the write model (commands) from the read model (queries), often with a read-optimised store.

Use when: you have heavy read requirements, different query shapes, or you need read isolation.

Event sourcing

Store every event that happened, not just the current state.

A simple mental model:

- You don’t store “current balance”.

- You store events like

DepositandWithdrawal. - The current balance is the sum of those events.

Use when: audit trails, time travel, or state reconstruction are real requirements.

When combined:

- Event Sourcing provides the truth (the event log)

- CQRS provides the fast view of that truth (read model)

Reality check: event sourcing is an operational commitment (schema evolution, replay tooling, backfills). Don’t adopt it because it sounds “modern”.

5) Which pattern should you choose?

| Goal | Pattern |

|---|---|

| Simple work distribution | Point-to-Point Queue |

| Reliable event delivery | Transactional Outbox |

| Complex cross-service logic | Saga Pattern |

| High-performance read/write | CQRS |

| Audit trails & replayability | Event Sourcing |

6) Summary (what matters)

Distributed messaging isn’t just about moving bits from A to B; it’s about managing failure and state.

Start with simple pub/sub for decoupling, and only move to Sagas or Event Sourcing when business complexity genuinely demands it.

7) A practical 2026 checklist (what actually helps)

If you’re modernising a system this year:

- Prefer async messaging at service boundaries where latency and coupling hurt.

- Use Transactional Outbox to avoid dual-write inconsistency.

- Make handlers idempotent by design.

- Introduce Sagas when workflows span services—pick orchestration when governance/debugging matters.

- Add observability early: correlation IDs, structured logs, and consumer lag metrics.

If you’d like help designing a messaging strategy that’s resilient and operable, reach out via /contact.